My drying rack was always practical—but oh, how it irritated me. Its plastic wheels never cooperated, and every threshold became a battle of rattling metal and collapsing legs. One day, as I struggled with it yet again, I thought, "There has to be something better that takes up less floor space."

Enter the "fregoli"—a traditional Hungarian ceiling-mounted drying rack from my childhood. But commercial options disappointed me—either ugly plastic contraptions or overly complicated motorised units priced like sports cars. And the memories also weren’t great: nylon cords frayed and tangled, the constant threat of falling, and a user experience so frustratingly poor it felt like punishment every time. Surprisingly, this very memory sparked my inspiration. Could I create something practical, beautiful, and enjoyable to use?

Although the initial CAD sketches looked promising, transferring the plans onto the actual wood felt strangely off. Trusting my instincts, I kept the geometric logic but adjusted the spacing parameters on the fly. I'm discovering more and more how important it is for me to plan thoughtfully, yet still leave room for improvisation and intuitive choices.

With many curves, arches, and rounded corners, I initially cut the first piece freehand using a jigsaw and sanded it meticulously until it felt just right. I then used this piece as a template for the rest, routing them precisely with a templating bit. Realising how effortlessly I could reuse the leftover freehand-cut edges for subsequent pieces was incredibly satisfying—a tangible indicator that my jigsawing and routing skills have genuinely leveled up through steady practice. This step felt particularly important, marking a clear increase in my confidence thanks to continuous learning and practice.

At the lumberyard, I stumbled upon heat-treated oak dowels: a deep, rich colour, and a comforting scent intriguingly reminiscent of something I could not place my finger on yet. Paired with the leftover birch plywood, I envisioned the striking contrast between the dark rods and the plywood’s layered edges.

Sanding the rods was something I dreaded initially, but building a simple jig around an inverted orbital sander turned a tedious task into a surprisingly efficient one. Hours into the process, I realised why the smell seemed so oddly familiar: heat-treated oak first smells like something freshly baked, then immediately like some very luxurious whiskey. That sensory discovery alone made the tedious sanding feel worthwhile.

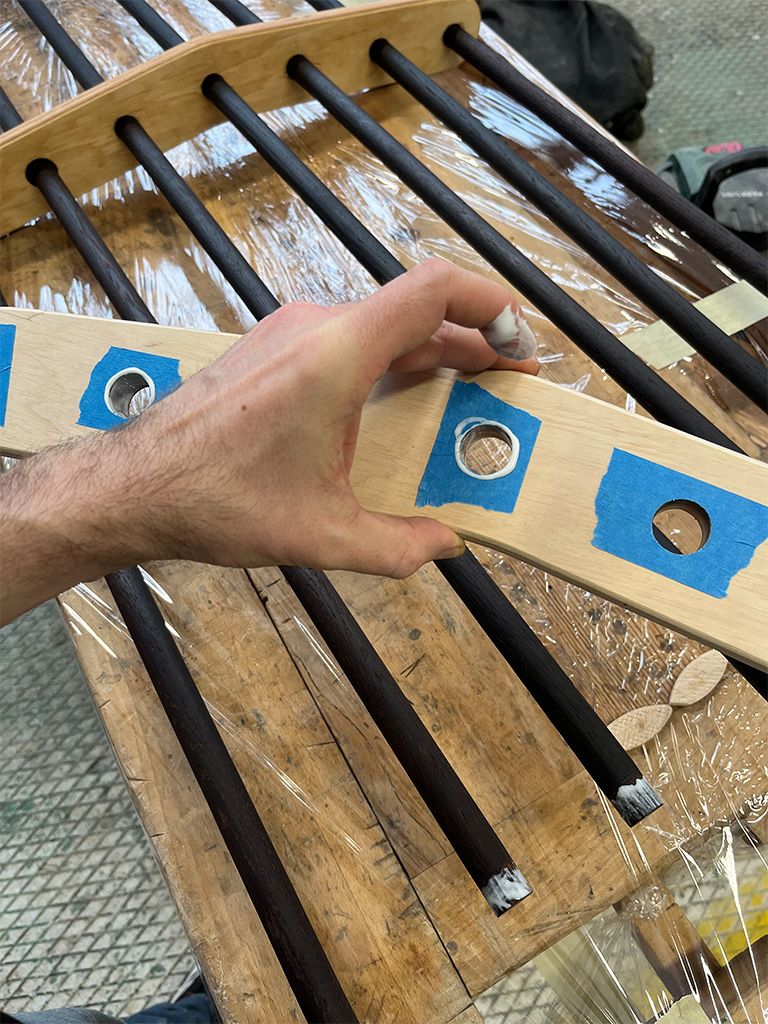

My favourite design detail: a sliding centrepiece. I wanted stability without sacrificing the flexibility to dry larger towels or sheets. By slightly widening the centre holes, I achieved a snug yet adjustable fit for the oak rods.

As always, there were unexpected challenges. Double-sided tape wasn’t strong enough to hold the pieces together for template routing, forcing me to improvise with screws that doubled as very handy centre markers. And when one oak rod snapped due to a hidden knot, the spare piece I instinctively bought saved the day—even presenting me with an opportunity to test whether PVA glue will bond to heat-treated oak.

Mounting the rack was a saga in itself. After hours drilling into the stubborn ceiling, dodging iron rebars, and getting mortar in my ears, the pulley system finally held securely. It was exhausting, and something I'm not really looking forward to doing again.

Looking at the completed fregoli and feeling the texture of the wood fills me with quiet satisfaction. Sure, there are a few details I'd approach differently next time, but right now, I'm resisting the urge to immediately chase perfection. I'm enjoying the imperfect beauty of what I’ve created, content in knowing that it already brings me joy.

Lifting the rack for the first time was not the moment satisfaction hit me, but the next day, when I stepped into the room and saw how it transformed the whole atmosphere. The contrasting woods, the arching crosspieces, and the black lift strings create an intriguing shape resembling the ribcage of some graceful sea creature, casting intricate, ever-changing shadows across the room. The hardoils need a few weeks of curing to completely seal the woods from moisture, and now I find myself looking forward to laundry days, simply for the joy of interacting with something I've made with care.

Creating this drying rack was particularly meaningful because it marked my first entirely original design—not a remix, nor inspired by something I'd seen elsewhere. Having the freedom to draw directly onto the wood, cut freehand, and make intuitive changes on the fly was liberating. It feels like a personal milestone: a confirmation that I can create something with confidence, from concept to finished object, that will live up to my (sometimes unrelenting) standards.

Some friends asked if I’d consider making more to sell. But part of me knows the joy lies in the creation itself—the planning, the woodworking, the problem-solving—not in mass production. Sure, I might enjoy creating another one, perhaps refining the process, working more efficiently. But by the third repetition, I suspect I'd already be redesigning it for CNC manufacturing and finding ways to simplify construction for outsourcing. Honestly, I'd rather just share the design files openly online, making it accessible for others to replicate and improve freely. Maybe this makes me a terrible businessman—but I’m very much at peace with that idea. Perhaps that’s a good lesson learned: the things I love most lose their charm when mass-produced.

So here it hangs—useful, elegant, mine. A reminder that surrounding myself intentionally with beautiful things that reflect back the qualities I want to nurture in myself is a worthy aspiration.